Introduction

Planning a vessel’s voyage is a critical detailed exercise, and the main goal is to ensure safe and efficient passage between two ports. The Master has the responsibility for the vessel voyage planning, but very often he delegates the actual voyage preparation to one of the junior offices on board, acting under his supervision and approval.

Proper passage planning includes the following four steps:

- Appraisal

- Planning

- Execution

- Monitoring

Any omission or underestimation of the any on them can lead to putting the vessel, her crew, and cargo in imminent danger. There are multiple considerations to be taken care of: Waypoints, Voyage data, Arrival/Departure port information, checking the weather forecast, checking the navigation/pilot charts, checking the vessel’s departure/arrival draughts, checking the cargo for any restrictions of carriage, operational restrictions along the route, etc.

The whole process involves so many checks that it is easy to lose track or miss a small but important detail. In this article, we’ll shed light on the important aspects of appraisal and passage planning stages and how best to take care of them.

Basic voyage Information

The first step is gathering the basic voyage-related information and making sure all data is available. This will involve the basics like:

- Voyage departure and arrival ports;

- Any intermediate port expected to be visited (bunker, supplies, crew change, etc.);

- Checking that all the required charts/sailing directions/ various nautical publications are available and up to date;

- Expected vessel draft during the voyage and any changes;

- Checking the maximum permitted drafts at departure/arrival ports and any other port-specific information provided by agents, guide to port entry, or other specific publication;

- Checking the bunker required for the voyage (quantity and type), available bunkers on board, and any need for deviations due to bunkering operation;

- Deviations required for changing ballast and/or cleaning/preparations of cargo compartments.

The above information has to be provided/confirmed aligned with various pasties on board the vessel and ashore – Master, Chief office, Chief Engineer, vessel’s operational, technical, supply, and crew departments, and port agents.

Appraisal Stage

The devil lies in the details: this is as true for passage planning as it is for any other endeavor. In this stage, it is important to get down to the details of every aspect of the passage plan.

The first step is to consult the Weather routing chart, Weather forecast, Ocean passages of the world, Load line zone chart, sailing direction, and small-scale charts in order to make a raw selection of our route and waypoints.

The second step is to transfer the already selected raw waypoint to relevant large-scale navigational charts, updated with all available T&P notices, local navigational warnings, etc. At this step, we need to identify any clashes between the selected route and areas, which are prohibited and/or dangerous for navigation for our vessel, and also ensure following the various applicable TSS and general traffic directions in the area.

Completing the above steps, we have gradually moved from the appraisal to the passage planning stage.

Planning Stage

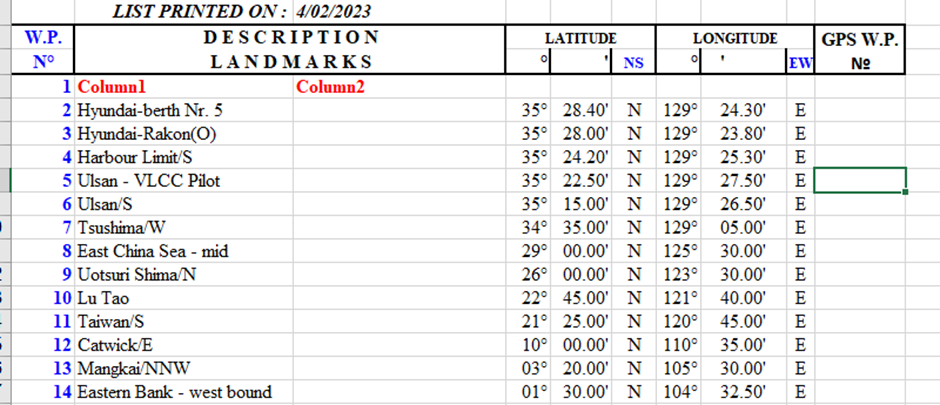

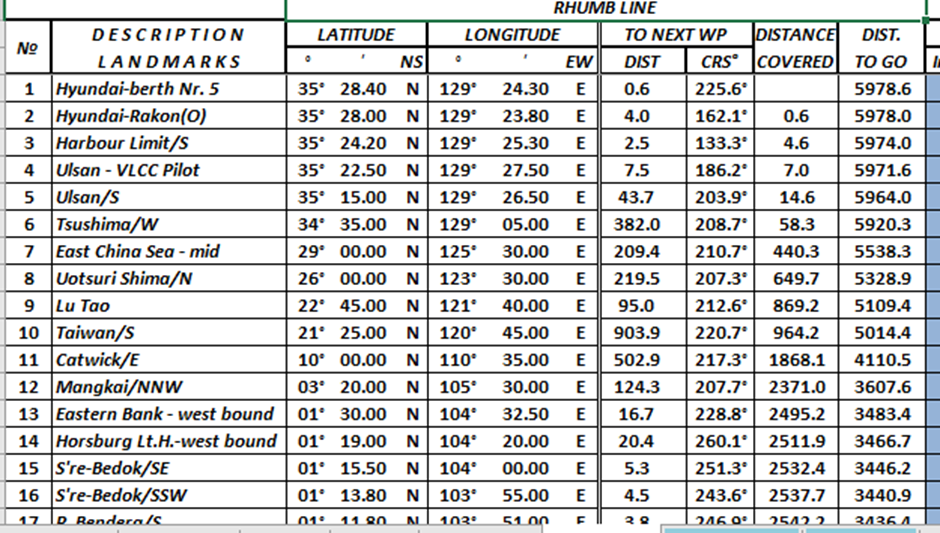

Once the passage plan and waypoints have been selected, the next step is to calculate the distances and course between them. For small to medium distances normally we calculate using the Rhumb line, but for ocean passages, it’s advisable to use the Great circle method.

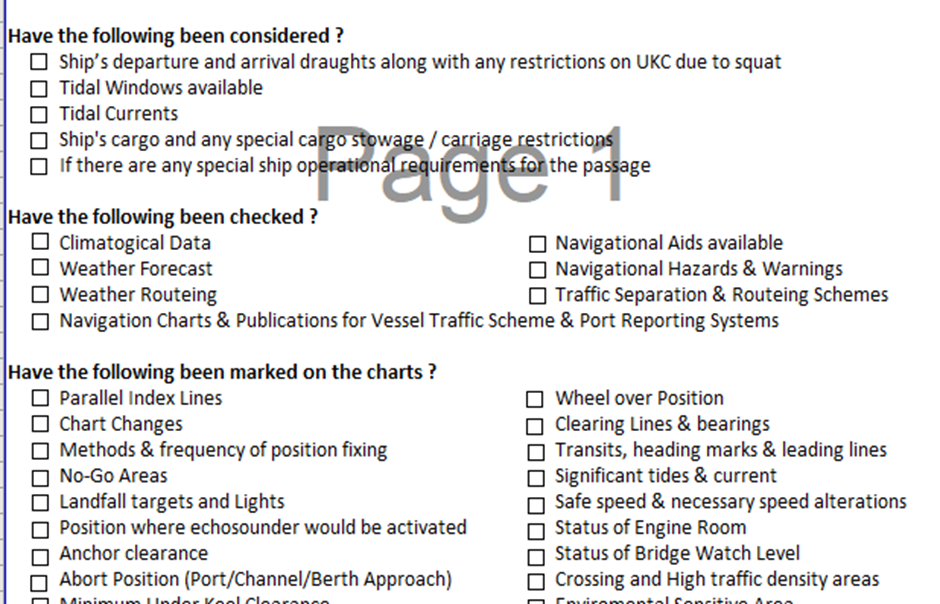

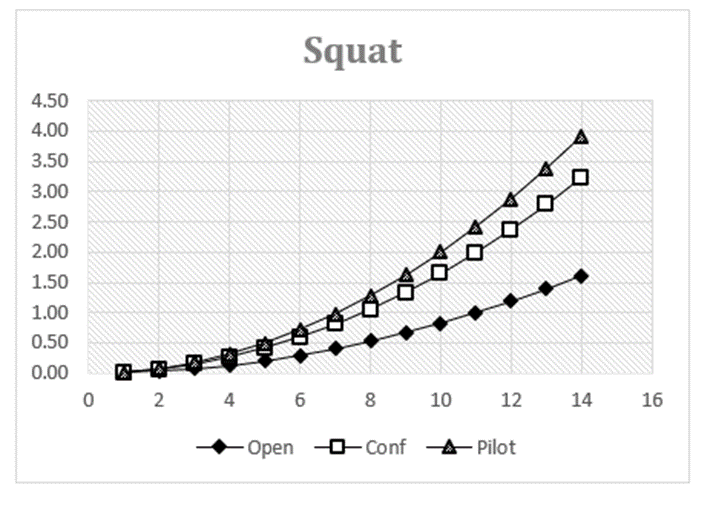

During the stage of selecting the waypoint and calculating the course between them, we need to keep in mind the vessel’s maneuvering capabilities and restrictions ( turning radius, expected speed for the legs, draft, squat effect, etc.). if required and possibly additional waypoints can be included in order to avoid sharp turns in confined/restricted areas for navigation.

During the passage stage, it’s good practice to identify and plot the chart’s additional information, which can facilitate the passage execution and monitoring.

Such information can include but is not limited to the following:

- Parallel Index Lines

- Chart Changes

- Method & frequency of position fixing

- No-Go-Areas

- Landfall targets and Lights

- Position for activating the echosounder

- Contingency anchorage

- Safe speed & necessary speed alterations

- Changes in engine status or bridge manning

- Entering/leaving Environmental Sensitive Areas

- VTS & reporting points

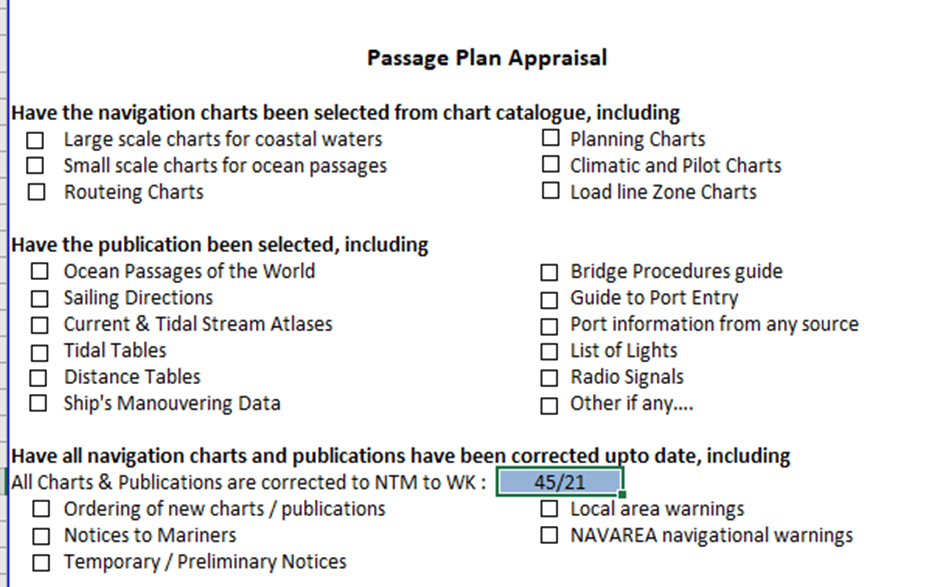

It is ideal to create a checklist covering the different aspects of the passage plan appraisal and planning stages in order to be sure that you have not omitted any important information.

The checklist may look somewhat like the below:

Maintaining Records

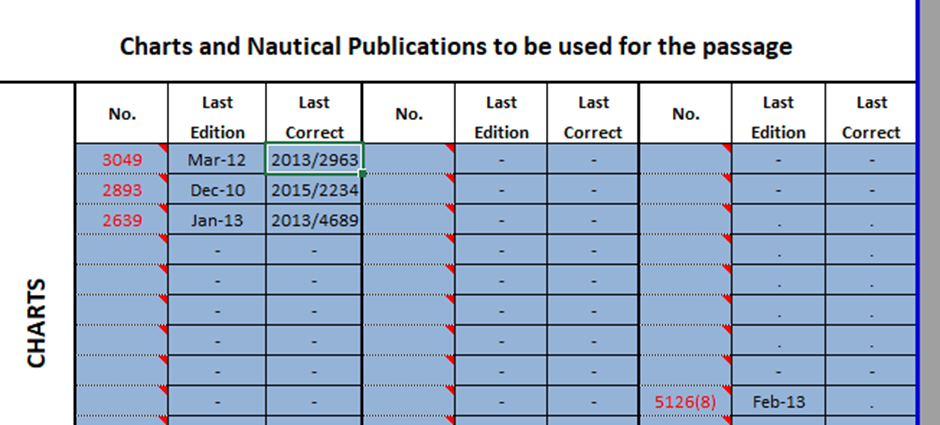

It’s very important that updated records of all input documents be used. Charts and publications used should be the latest edition, and it is ideal to record and double checked that they are corrected up to the last available correction.

For example, the publications used, their edition and corrections, etc can be recorded in a table like the one below:

Squat and Air Draft

Last but not least, it is important to calculate beforehand the expected under-keel clearances and air drafts in order to avoid any surprises.

A squat may reduce the UKC significantly, which will have an effect on vessel maneuverability. Also, we have to be aware of the company or local authorities’ minimum UKC policy, which can lead to tide restriction departure/arrival from ports or passing over shallow banks/areas.

The squat mainly depends on vessel speed and area of operation (open or confined water), so it can be controlled to some extent by choosing the appropriate speed.

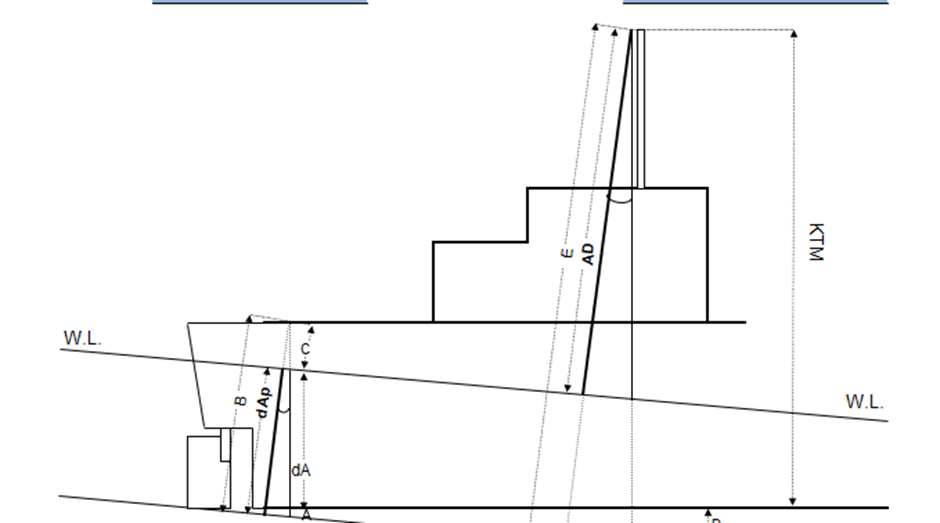

Air draft restrictions are applicable when the vessel is passing under bridges or electrical cables.

Air drafts will depend on the vessel draft and trim, the only way to control the air draft is to adjust the draft and trim if possible.

Voyage planning is a comprehensive exercise and needs to be meticulously carried out. It has to be kept in mind that what is acceptable and safe for a small container vessel can be totally unsafe for a VLCC tanker. Furthermore, the oceans, seas, and ports are constantly changing due to natural or human factors, and the area, where you have passed safely a few months ago, now can be dangerous for navigation.

With the above-taken care of, risks can be averted and a smooth sail is more likely.

Please take out some time to explore TheNavalArch’s passage planning tool:

Brilliant and useful article on voyage and passage planning of ship. Without a proper plan, the ship and its crew will be in industry. This can create a bad impression of the maritime.

Sadly the squat is again rather simplistic and the supplied forula is the Simplified Barrass formula. There are many better ones (last count 15 formulae) but this is safe for outside of port limits and is at least very conservative.

Hi Jonathan

Thanks for your feedback. Can I urge you to write another article about squat that gives a more holistic perspective?

Prem Shankar

TheNavalArch