(This article originally appeared in June 2018 edition of Marine Engineers Review, Vol 12, Issue 7, Journal of The Institute of Marine Engineers (India), and is being reproduced here for readers of TheNavalArch’s blog)

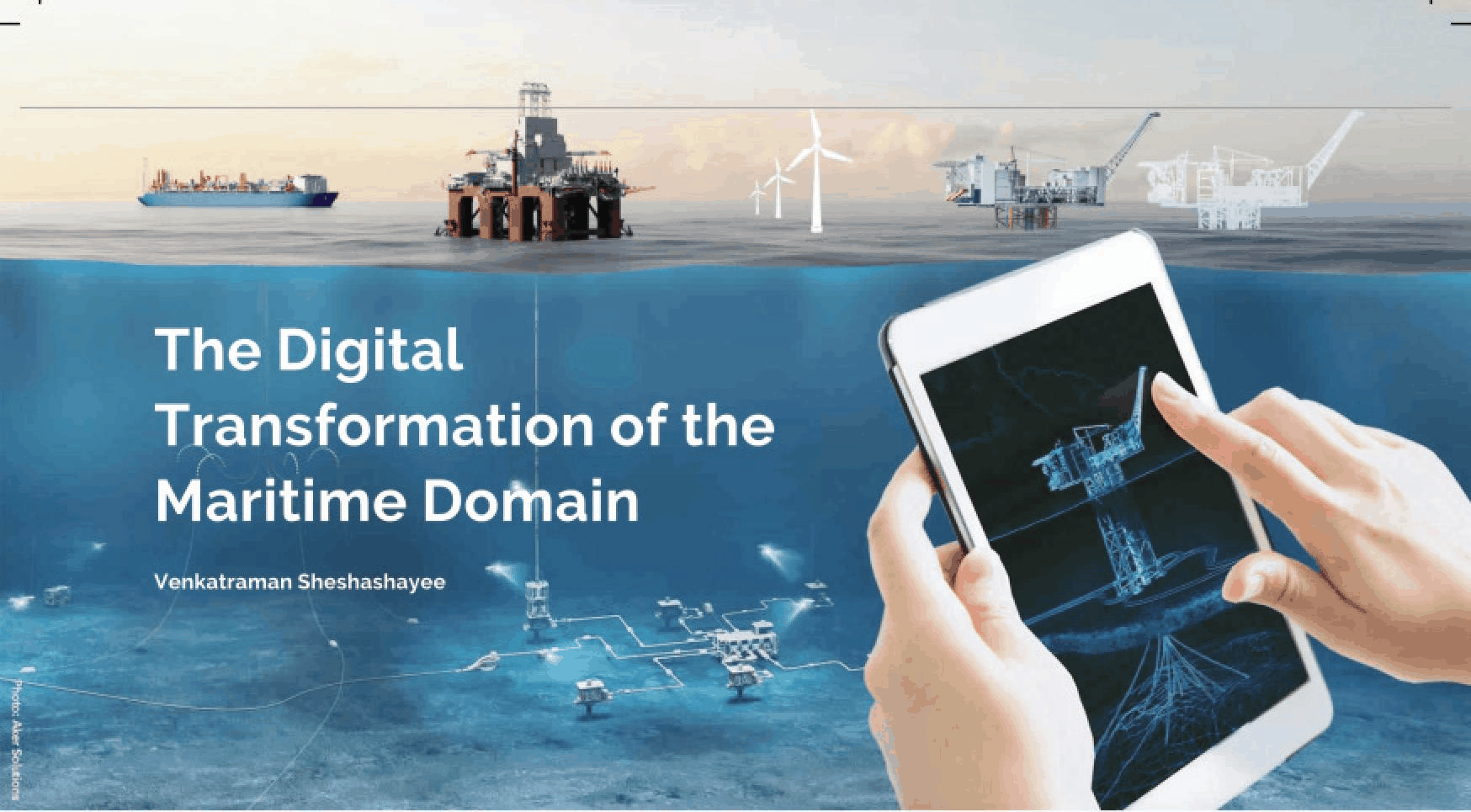

The maritime domain is gradually coming to terms with the dawn of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. An industry that has largely resisted or ignored technology is being forced to reconsider its stand. The adoption of technology in the maritime space is driven primarily by two factors – the need to become more cost efficient and the looming shortage of traditional skills. Both these factors have the potential to have serious and lasting impact on this sector, and technology is being seen as a panacea.

What do we mean by ‘technology’, which is such a broad term that encompasses anything from steam engines to brain computer interfacing? Which aspects of technology are threatening (or promising) to reboot the maritime world?

Artificial Intelligence

First, there is Artificial Intelligence. Al subsumes a broad set of technologies incorporating machine learning, neural networks, cognitive networks, natural language processing, advanced robotics, etc. Each of these is a vast subject on its own. Together, they have the potential to change the world in alarming and amazing ways. Al, properly deployed on vessels, can lead to smart equipment capable of diagnosing themselves, ships that can choose the most economic route to their destinations without (and even in spite of) human intervention, vessel convoys forming and separating when required, cargoes being allocated to vessels to maximize capacity utilization and minimize ton-miles. The list is practically endless. We can be sure of one thing – Al will impact every single aspect of the maritime value chain sooner than most of us expect.

Transiting to Al is unlikely to be smooth and seamless. There are and will be myriad challenges. Who will lead? Who will drive? What standards will be followed? What role will IMO play? What role will flag states play? How will Al impact seafarers? How will it affect on-shore managers? To what far reaches of the value chain will AI extend? How secure is it? Who will guard it? What can happen if there is a breach? Who is responsible, the ship’s crew or the vessel owners or the software developers?

Sensor Technology/IoT in Maritime Industry

Second, there is situational awareness through sensor technology. While this can be seen as a part of AI, it is also distinct in many ways. Sensors enable physical systems to perceive the world around them and help them respond and react in the most beneficial mariner possible. Sensor technology is what allows driver less or autonomous cars to wend their way safely on busy roads. It allows the monitoring of the aged and the young, the tracking of wellness, the surveillance of criminal acts, the disruption in weather patterns.

Sensor technology is not new. All of us have encountered it, sometimes on a daily basis. If you have washed your hands in an airplane toilet, you have met and used sensor technology. The proliferation and the interaction and the data generation are what make this truly transformational.

Here again, there are challenges that the quality and accuracy of data, the seamless connectivity between sensors and their servers, the integrity and resilience of sensors in diverse environments, the security of the data – all of these are issues that need to be considered, dealt with and resolved.

Data Connectivity in the maritime world

Third, for Al and sensors to fulfil their potential, we need connectivity. Currently, maritime connectivity is pathetic, even if one is being kind. The current technology in use (FBB, Satcom) were state-of-the-art in the nineties. Higher data rates, lower latency, satellite wi-fi these are just a few changes that are on the horizon.

As connectivity improves, onboard systems and sensors will start integrating into the Internet of Things, and by doing so, gradually become more intelligent, predictive, responsive and capable.

Maritime Cybersecurity

Four, to ensure that all the above technologies are secured and safe. Cybersecurity will need to go into overdrive.

Any disruption to connectivity or malicious interference can have devastating outcomes. As the spread of sensors and Al increases, security becomes increasingly critical as an attack can disable, take control or even destroy remotely without warning.

Technologies that are currently being deployed ashore such as adaptive security architectures and Al enabled reactive security will need to be embraced and quickly. Insurance will need to adapt. Standards will need to be set. Security infrastructure and behavior will need to be monitored and audited.

Regulatory Regime, and the need to collaborate for emerging technologies

Overlaying all these is the regulation of emergent technology. Traditionally, regulation lags technology. While this may not be life threatening in cases of privacy in social media and speculation in crypto-currency, it is absolutely critical in a global, disconnected, remotely managed sector like maritime. Class Societies, Flag States, IMO, Insurance Companies, Port State Controls, OEMs, Shipbuilders, et al have to collaborate and coordinate to establish clear norms to manage the advent of and spread of transformative technologies. While doing so, they have to be careful not to smother it with restrictions and risk averseness. Maritime regulation needs to learn to manage risk not avoid it. Appropriate regulation can help safeguard against non-conforming quality and deviation from standards.

It can help allocate ownership and responsibility. It can help define liability and its root. Some classification societies have already started work in this area, but a much more concerted and orchestrated effort is required.

The virtual revolution will change shipping in ways that we, even today, do not anticipate. The benefits are tremendous – enhanced safety, lower operating costs, prediction and pro-action, increased efficiency, real time oversight. The path to this nirvana is unlikely to be paved. The disruption that the maritime world is quaking in anticipation about is not so much the technology itself: rather, the uncertain steps and painful stumbles that we will encounter getting to where we should be.

Disclaimer:

The views, information, or opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of TheNavalArch Pte Ltd and its employees

This article originally appeared in June 2018 edition of Marine Engineers Review, Vol 12, Issue 7, Journal of The Institute of Marine Engineers (India), and is being reproduced here for readers of TheNavalArch’s blog.

Venkatraman Sheshashayee

Former CEO | Mentor to Boards, Promoters and Professionals

Venkatraman Sheshashayee (Shesh) is Managing Director of Radical Advice, a business transformation advisory based in Singapore. He has over 34 years of experience in manufacturing, shipping and offshore oil & gas.

Shesh’s previous roles include CEO & ED of Miclyn Express Offshore, CEO & ED of Jaya Holdings Limited and Managing Director of Greatship Global.

In his new avatar, Shesh helps mentors Boards, Promoters and Professionals and helps them achieve their potential.

Shesh is the author of the ‘CEO Chronicles’ series on navigating careers and the ‘What Women Want’ series on gender awareness, published on LinkedIn and Medium.

He can be reached at vshesh@radicaladvice.net

TheNavalArch Interview Series: Capt Robin Perera

TheNavalArch's Interview Series is an endeavor to get insights from the best engineering and business brains in the industry and present them to its users for the larger benefit of the maritime community. Leaders share their experiences and ideas that readers can gain...

Offshore Installation Vessels Stability Considerations

OFFSHORE INSTALLATION VESSELS STABILITY CONSIDERATIONS By Alan Crowle, BSc, MSc, MScbyRes, CEng, CMarEng, FRINA, FMAREST, FSCMS University of Exeter, College of Engineering, Renewable Energy Group INTRODUCTION The temporary phases of an offshore structure transport...

TheNavalArch Interview Series: Mr Victor Valera

TheNavalArch's Interview Series is an endeavor to get insights from the best engineering and business brains in the industry and present them to its users for the larger benefit of the maritime community. Leaders share their experiences and ideas that readers can gain...

TheNavalArch Interview Series: Mr Steven Lu

Mr. Steven LuManaging DirectorEpoch Offshore Engineering (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. TheNavalArch's Interview Series is an endeavor to get insights from the best engineering and business brains in the industry, and present them to its users for the larger benefit of the...

TRANSPORT VESSELS FOR FLOATING WIND

By Alan Crowle, BSc, MSc, CEng, CMarEng, FRINA, FMAREST, FSCMS Masters by Researcher, University of Exeter, College of Engineering, Mathematics and Physical Sciences, Renewable Energy Group SUMMARY Floating wind turbine construction is a large logistical exercise. The...

TheNavalArch Interview Series: Mr. Balakrishna Menon

Mr. Balakrishna MenonEngineering Director Mooreast (Asia) Pte Ltd TheNavalArch's Interview Series is an endeavor to get insights from the best engineering and business brains in the industry, and present them to its users for the larger...

Floating Rice Fields, the quest for solutions to combat drought floods and rising sea levels

by Lim Soon Heng, BE, PE, FSSS, FIMarEST Founder President, Society of FLOATING SOLUTIONS (Singapore) Abstract Amazing as it seems, there is a case for growing rice on floating platforms in the sea. The capital expenditure to develop this is offset by the opportunity...

CAPSIZE OF LIFTBOAT IN TRANSIT

This paper was originally presented in the 27th Offshore Symposium, February 22nd, 2022, Houston, Texas Texas Section of the Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers It has been reproduced here for the readers of TheNavalarch INTRODUCTION In 1989 a Class 105...

FLOATING WIND TURBINES -TRANSPORTATION AND INSTALLATION ENGINEERING

By Alan Crowle, BSc, MSc, CEng, CMarEng, FRINA, FMAREST, FSCMS Masters by Researcher, University of Exeter, College of Engineering, Mathematics and Physical Sciences, Renewable Energy Group Summary Floating offshore wind turbines are an emerging source of marine...

Preparation for Dry-docking of an oil tanker: A Chief Engineer’s approach

Introduction Dry-docking of a vessel is required at every 5 yearly intervals to carry out inspection of hull, propeller and other components which are normally submersed in water all the time. This is a requirement by ship’s classification societies. However, some...