Automation is in good servant but a bad master!

By Dr L R Chari, ex-Executive Director of Shipping Corporation of India (SCI)

*This article originally appeared in June 2018 edition of Marine Engineers Review (India), the Journal of Institute of Marine Engineers India. It is being reproduced here for the readers of TheNavalArch’s blog.

Abstract

A new kind of ship is taking to the seas and mariners are not sure what to make of it. Is it safe? How will it get along with other vessels and smaller crafts in the vicinity? Will it really shake up the maritime transportation business? What impact will it have on the seafaring profession? Is there a Legal framework in place to allow autonomous shipping? These are some of the questions being asked about autonomous shipping. This paper tries to make an objective assessment of the problems and prospects of the concept of this apparently fancy mode of maritime transportation.

1.0 Introduction

Just imagine a situation such as this – It is a dead dark December night somewhere in the middle of the Pacific Ocean where a massive crude oil tanker receives the latest weather report about a huge storm brewing ahead. Quietly, the ship changes its course and speed, to avoid the worst storm and ensure an on-time arrival at its next port of call. The ship’s owners and the port authority at its next destination port are notified about the revised route and the expected time of arrival. As this giant ship nears the shore, it must correct its course once again – this time to steer clear off smaller fishing crafts on its starboard side. This may seem like just another routine day for trans-Pacific shipping but in reality, it is not. Nor is it a page out of a pulp fiction. This is a ship with no one onboard – it is an autonomous ship, which is commanded from a control center located on the other side of the globe, where technicians are monitoring and controlling the movement of this ship and other similar vessels via a satellite data link. Although autonomous or smart ships of this kind are the ships of the future, the question is not whether they will happen at all but when and how soon they will happen. Experts and engineers at the Rolls-Royce feel that the first commercial vessel to navigate entirely by itself could be a harbor tug or a ferry designed to carry cars a short distance across the mouth of a river or a Fjord and that this or similar ships will become commercially operational within the next couple of years. If things proceed as planned, fully autonomous oceangoing cargo ships are expected to routinely ply the world’s seas in a decade or two. Remotely controlled ships, piloted by people on shore. and self-controlled autonomous ships, are the latest beneficiaries of increasing digital connectivity and artificial intelligence. The recent developments of smart sensors and actuators, digital telecommunications and computing as well as Internet of Things (IoT) that have sparked interest in a range of autonomous vehicles including cars, planes, helicopters and trains, have now turned their attention to shipping. Companies and academic researchers around the world are working overtime to turn these ideas into reality.

2.0 Pilot Projects in the Pipeline

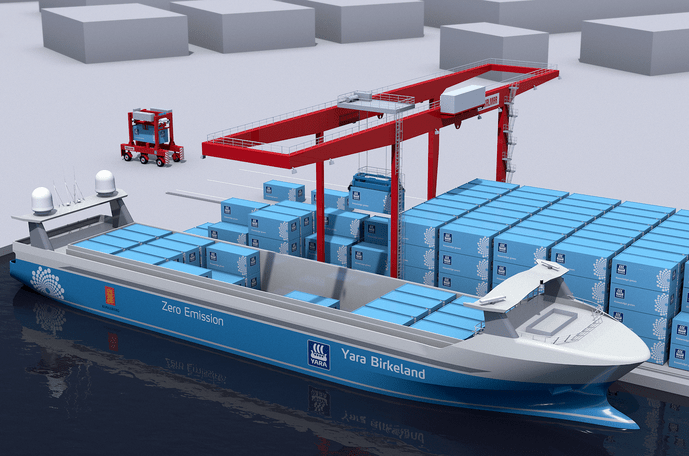

Rolls Royce has initiated a joint industry project in Finland called Advanced Autonomous Waterborne Applications (AAWA). Read more about AAWA here. The participants will attempt to create the most appropriate technology for a remotely controlled or fully autonomous ship that is expected to operate in coastal waters before the end of the decade. The European Union’s Maritime Unmanned Navigation through Intelligence in Networks (MUNIN) project, led by the Fraunhofer Center for Maritime Logistics and Services in Hamburg, is assessing the technical, economic, and legal feasibility of operating an unmanned merchant vessel autonomously during an open-sea voyage. In addition, researchers at the DNV GL, an international ships classification society, are exploring the feasibility of using unmanned battery-powered vessels to transport freight along Norway’s long coastline. Yara Birkeland is expected to be the world’s first fully electric autonomous container ship, with zero emission. M/S KONGSBERG will be responsible for providing all the key enabling technologies including the smart sensors and integration required for both remote as well as autonomous control of this ship, including the electric drive, battery bank and propulsion control systems. Yara Birkeland is expected to operate initially as a manned vessel and then shift to remotely operated ship in 2019 and finally move to full autonomous operations from 2020. China’s Maritime Safety Administration and Wuhan University of Technology have partnered in their Unmanned Multi functional Maritime Ships Research and Development Project. Their goal is to find ways for autonomous ships to be used within China’s commercial and military maritime sectors.

Yara Birkeland: World’s first zero-emission and autonomous container vessel (credits: yara.com)

3.0 The Pros & Cons of Autonomous Shipping

There is a lot of work being done on autonomous ships. But according to veteran mariners’ way of looking at the pros and cons of the shipping business as a whole, the cons of autonomous shipping at this time could out number the pros. While, on the one hand, the pros of autonomous shipping could be shorter port stay, faster turn around, no crew cost hence lower operating cost, lower freight rates, no accidents due to human error, no dependence on crew supplying countries and agencies, and full control of the ships by their respective owners; on the other hand the cons of autonomous shipping could be high vulnerability to cyber attacks and increased piracy threats to ships, fear of hijack by unscrupulous elements, possibility of accidents due to machine failure, increased scope for maritime frauds, no guarantee of cleaner and safer seas, no employment for sailors, search and rescue operations at sea in jeopardy, potential danger to all manned ships, smaller crafts, fishing vessels etc. in the vicinity, safety and security issues for ships operating in conflict zones and last though not the least no legal framework in place as yet. Be that as It may, a perspective about the nature of the exciting efforts being put in by the developers of autonomous ships is given in the following paragraphs.

4.o Autonomous Ships of the Future

The size of ships’ crew has been decreasing for some time now, and soon some large vessels may sail without anyone on board. Ships designed to be controlled remotely and self -navigated ships will look distinctly different from today’s ships because they will have no accommodation space due to total absence of crew. Soon, advanced automation will help battery-powered ferries now being built for the Norwegian company Fjord1 to make their crossings using electrical energy in the most efficient manner possible.

4.1 Advantages of Autonomous Ships

Autonomous or smart ships or unmanned ships as they are called, are, according to the developers of this concept, expected to be safer, more efficient, and cheaper to run. According to a report published in 2012 by Allianz, the Munich-based insurance company, between 75% and 96 % of marine accidents are a result of human error, often due to work fatigue of the crew members. The report of Allianz can be downloaded here. Remotely controlled and autonomous ships are expected to reduce the risk of such human errors or mistakes and along with it the risk of injury and even death to members of the crew as also danger to the ship itself. Another advantage perceived by the developers of the concept of remotely controlled and autonomous ships is that they can be designed with a larger cargo carrying capacity and lower wind resistance due to absence of accommodation for the crew. This will make the ship lighter and sleeker, cut fuel consumption, reduce its construction and operation costs, and facilitate designs with more space for cargo. Finally, a smart ship, according to its developers, will show owners and operators a way to respond to the growing perceived shortage of mariners. With more and more mechanical and electronic systems onboard, ships are becoming increasingly complex, needing skilled technicians to keep the ships working. At the same time, seafaring as a career is becoming less attractive, with fewer people wanting to spend weeks or months at a time away from home and family. Remote and autonomous operations of ships could facilitate the transfer of jobs requiring high levels of education and skills to ports of call or to operations control centers on shore, thereby making such careers more interesting to young people entering the industry.

4.2 A Poet’s Musings on Autonomous Shipping

The opening lines of the poetry titled ‘SEA FEVER’ by the famous 19th century poet John Masefield state

‘I must go down to the seas again , To the lonely sea and sky

And all I ask is a tall ship, And a star to steer her by’

Now if autonomous ships become a reality and if John Masefield were to reincarnate in the 21st century as a poet all over again, this is how he would re-phrase the opening lines of the poem re-titled ”SEA FEVER-REVISITED’

Must I go down to the seas again? To the crowded sea & sky.

When I have an autonomous ship, and there are satellites to steer her by.

4.3 The Challenges for Autonomous Shipping

It will not be roses, roses all the way for autonomous shipping. While all the technological building blocks are in place to construct and control smart ships, what could prove to be more challenging, though, are the regulatory changes required to allow such ships to operate safely. At this point in time, global shipping regulations are unclear about whether these ships would be permitted to operate, how they could be insured, and who would be legally liable in the event of an accident. The biggest challenges, however, for autonomous shipping will be cyber attacks and piracy. As regards cyber attacks, an autonomous ship is as vulnerable to such attacks as any computerized system in a shore-based establishment is. All the computerized and networked shipboard systems are potential targets for cyber attacks, which can lead to disastrous consequences. Anticipating the need to address cyber threats on a priority basis, the IMO has taken the initiative to address the cyber issues through the issuance of detailed guidelines in 2017. As for piracy attacks, it would be too presumptuous on one’s part to assume that because of the high degree of sophistication of autonomous ships, pirates will not be able to attack them. Pirates are capable of devising their own methods to beat the system. Hence the need to suitably augment the vigilance system by the Navy and the Coast Guard, while bearing in mind the fact that it is impossible for the Navy and the Coast Guard to protect every square inch of the oceans. Protecting from hackers the data streams and the ship’s systems to which they connect will be yet another big challenge that will also need to be addressed lest troublemakers should divert ships from their routes, or worse, make them collide with other ships or offshore oil/gas platforms or offshore wind farms.

5.0 The Need for Regulatory Framework

As autonomous ships are expected to be the form of marine transportation in the near future there is an urgent need to put in place a suitable regulatory framework for governing the operations of these ships in high seas. Along with members of the AAWA project, at least two other groups in Europe are looking at changes to regulations that would address the serious issues as Outlined above. A group called Safety and Regulations for European Unmanned Maritime Systems (SARUMS), led by Sweden with six other participating countries, is one such organization. In the United Kingdom, the Maritime Autonomous Systems Regulatory Working Group has been carrying out similar exercise. The ultimate aim is to ensure that the next substantial revision of the International Convention on Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS)—the rules that govern international shipping- reflects these technological developments. Also, for similar reasons the IMO will be required to review and make appropriate changes to the COLREG, MARPOL, STCW, MLC, GM DSS and the UNCLOS conventions. The regulators debating these issues will clearly want to know just how safe autonomous ships will be. So the challenge now for the engineers is to combine relevant technologies to best effect to avoid all possible dangers to autonomous ships.

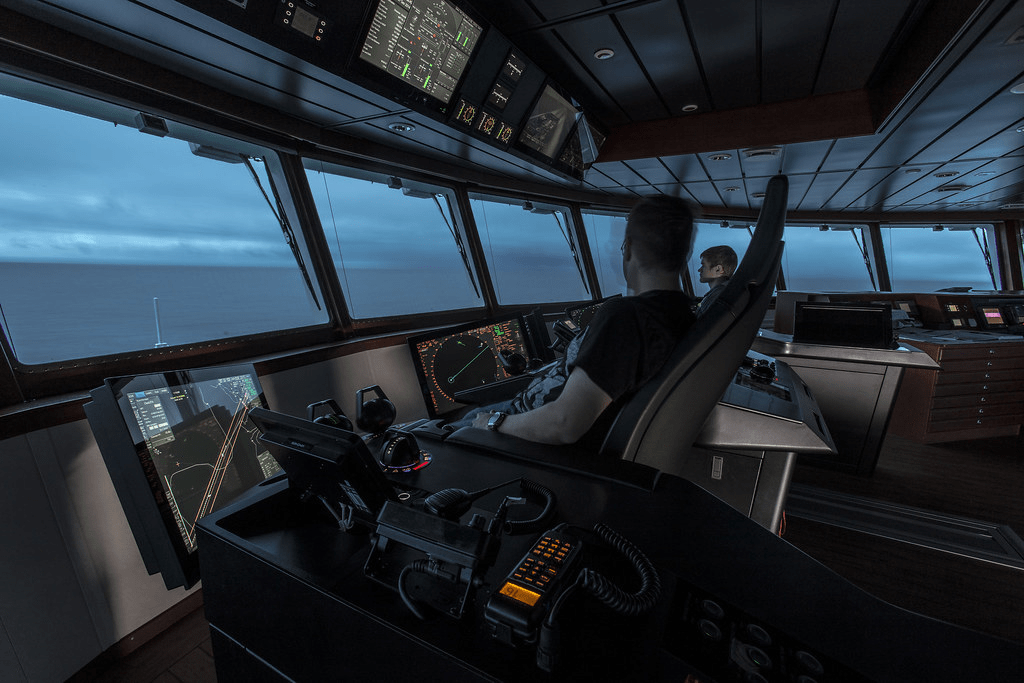

6.0 The Wheelhouse of the Future

When the time comes to control large oceangoing ships from facilities on shore, the centers set up for such remote operations might resemble the Rolls Royce’s Unified Bridge, which was installed initially on the platform-supply vessel Stril Luna. This vessel’s bridge offers a 360-degree panoramic view, with all the computerized controls & monitoring systems within easy reach. Maintaining good situational awareness & keeping the bridge uncluttered both help to improve the safety of operations. Vital to the development of remotely controlled & autonomous operations will be a ship’s ability to sense and communicate what is going on around it so that it can safely navigate to its destination, avoiding collisions along the way, and perform complex maneuvers, such as docking when it finally arrives at the port. Experts at Rolls Royce are working on situational-awareness systems that integrate imagery from high-definition visible-light and infrared cameras with LIDAR and RADAR measurements, providing a detailed picture of the ship’s immediate surrounding. This information can then be either transmitted back to a remote-operations centre where it would be presented to an experienced Captain or used by the ship’s onboard computers to generate the next appropriate course of action. The ship’s remote commander or its autonomous-navigation system would also take advantage of many other sources of information, such as position fixes from satellite navigator/GPS system, weather reports, broadcasts from other ships about their positions and identity. Ships’ crew members today are already using multiple data sources and electronic aids as part of their daily activities. Systems already exist to plot other vessels’ positions, assist with navigation decisions, monitor the ship’s main machinery, and ensure that the engines and other key auxiliary machinery are performing properly. In the future more data will be available from smart sensors embedded deep in the ship’s key systems, namely, its main engine, propeller, bow thruster, electrical generators, compressors, purifiers, cranes and other deck machinery. This information will help determine whether all the systems are working properly and in the most efficient manner possible. When a critical part starts to fail, preventative maintenance can be scheduled at the next port of call or, if need be, by dispatching people to carry out repairs while the ship is still at sea. There is no doubt that when the ship involved is autonomous or remotely operated, getting this data to shore in a timely manner is vital for its operations. Such ships will thus require constant real-time communications links. While satellite communications have been available to ships on the high seas for many years, service is now getting better with the availability of high speed data transfer facility. In particular, AAWA’s partner the INMARSAT launched its third Global Xpress satellite in August 2015, which gave the company the ability to support broadband data links almost anywhere in the world. So INMARSAT can provide future unmanned ships with high-speed broadband connectivity from space, just as it is doing for vessels today.

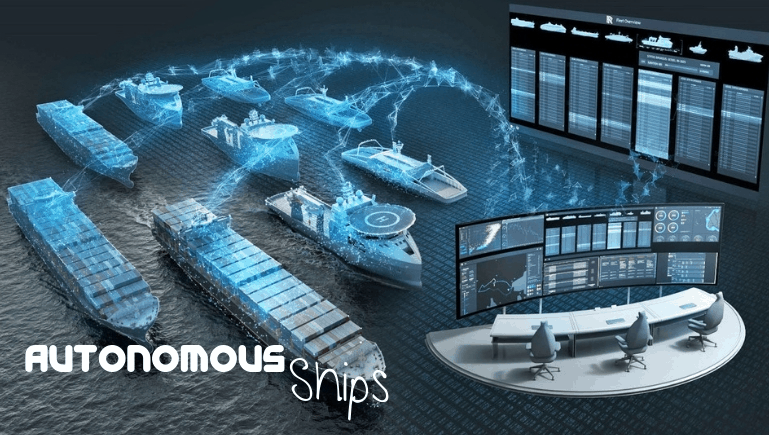

7.0 Remote Control Centers for Ships

Even when ships are able to operate completely on their own, there will have to be somebody ashore who can take charge if and when conditions demand. Different types of ships, or ships at different stages of their voyages will, in all likelihood, require very different levels of oversight and control. For instance, a cargo ship far out at sea will normally need little human supervision, with a single controller overseeing many ships at the same time. But a vessel operating in a congested shipping lane, close to shore, or while entering or leaving port will require much more care and full attention of an individual controller. As a consequence, an important technological component in all this is the development of remotely controlled systems and control centers. Building on the experience gained from work in the aviation, nuclear energy, and space exploration fields, and from constructing simulators used for training mariners, experts in Rolls Royce have been studying how to design such centers. Their configuration must take into account not only the ergonomics but also the ease of use and how to convey a realistic portrait of what is happening around the ship. To construct such remote-operations centers, Rolls Royce will also be taking advantage of what its engineers have learned while designing and building its Unified Bridge, which is a complete redesign of the traditional ship’s bridge – the one that provides a more comfortable, clutter-free, and ultimately safer working environment for mariners. The ship Stril Luna. a platform supply vessel (PSV) owned by Simon Mokster Shipping Company was the first ship fitted with Rolls-Royce’s Unified Bridge to sail for the first time in August 2014. Since then, the Unified Bridge system has been installed on tug – boats, mega yachts. polar research vessels as also on a new type of cruise-ship.

Stril Luna’s Unified Bridge (image credits: Flickr)

8.0 Multiple Schemes for Autonomous ships’ Design

It is unlikely that there will be a single scheme for building and operating smart ships. Some of these vessels could operate without any crew at all, and these ships will look radically different from current designs. Others will rely on a blend of autonomous and remote controlled vessels, sailing autonomously in open waters but falling back on remote control when more advanced maneuvers are required. Yet another type of vessels, such as cruise ships, will always require crew for customer service, safety, and reassurance. Manned ships of the future will have many of the technological features of the autonomous ships that will provide the people on-board with improved situational awareness thereby increasing the safety of the ship. The first smart ship to go into commercial operation will mostly use technology that is already available. A vessel of this kind will most likely ply in the coastal waters of a single ‘Flag State’ that can provide the legal basis for such a ship’s operation. This ship could be a ferry, a tug boat, or a coastal vessel sailing within confined waters. It could still have a crew on board who will be carrying out duties other than navigating the vessel. The Norwegian Maritime Authority and the Norwegian Coastal Administration have signed an agreement that allows for relevant sea trials to take place in the Trondheim Fjord, the first place in the world to be designated for the testing of autonomous ships. Meanwhile, in Finland, an association of the Finnish Marine Industries, together with the Ministry of Transport and Communications and Tekes (the Finnish Funding Agency for Innovation) has joined Rolls Royce and other companies to explore and develop autonomous marine transport in the Baltic Sea.

Image credits: maritimecyprus.com

9.0 Conclusion

Autonomous ships or smart ships with no crew onboard are a distinct possibility in the not too distant a future. But to reach this destination a few more milestones need to be crossed in order to make autonomous shipping absolutely safe, secure, reliable and legal. And before signing off it is worth pondering over this point If man himself is imperfect then can man-made devices be perfect?

References

Oskar Levander “Autonomous Ships on the High Seas”, IEEE Spectrum Volume 54, Issue 2, February 2017

Resources

- An article charting the timeline of development of autonomous ships: http://infomaritime.eu/index.php/2018/06/08/timeline-development-of-autonomous-ships/

- An article detailing the current projects: https://www.opensea.pro/blog/automated-ships

- A video of Stril Luna PSV fitted with Rolls Royce Unified Bridge: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uJv1jecTLyo

About the Author

Dr. L. R. Chary retired from the Shipping Corporation of India (SCI) as Executive Director. He has over 30 research papers published and is a recipient of several awards including the H S Rao Memorial Award given by the Institute of Marine Engineers (India). He has had a distinguished career and currently serves in the Board of several institutes.

Cargo Stoppers – why they are critical and how to design them

Stoppers and their critical role in seafastening of cargo Introduction A cargo transported on the deck of a ship is subject to many forces. These forces comprise of the inertial forces due to the ship motions – the three translations and three rotations – and the...

Are you chartering a tug bigger than necessary for your Barge?

Barges are one of the most frequently used means for transporting deck cargo of different shape, size and weight. While some barges are self-propelled, the majority is towed by another vessel called a ‘Tug’. Once an owner or charterer...

Fendering – an Introduction

In this two part article we will talk about Fendering, which is one of the basic but critical operations related to a ship. Fendering is, basically, protecting the ship’s sides from contact with another body (which can be another ship, jetty or quay wall). It can also...

Loadouts – An introduction

Image source: Flickr Loadout Operations - an Introduction Loadout is a term oft heard of in the marine/offshore industry parlance. Loadout is generally referred to the operation of transferring a Cargo or a Structure from the place of fabrication to a sea-borne...

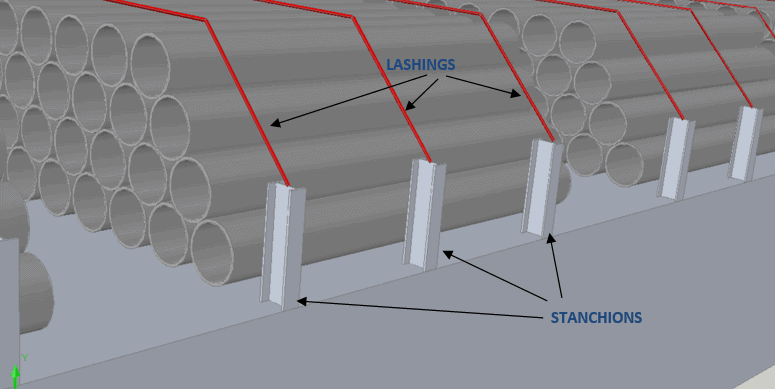

Introduction to Pipe Transportation – Part 3 (Engineering)

Introduction to Pipe Transportation - EngineeringIn Part 1 we learnt about pipes, while in Part 2 we learnt about Planning and Scheduling of pipe transport operations. In this part, we will learn about Engineering.Phase 3 – Engineering.Engineering for pipe...

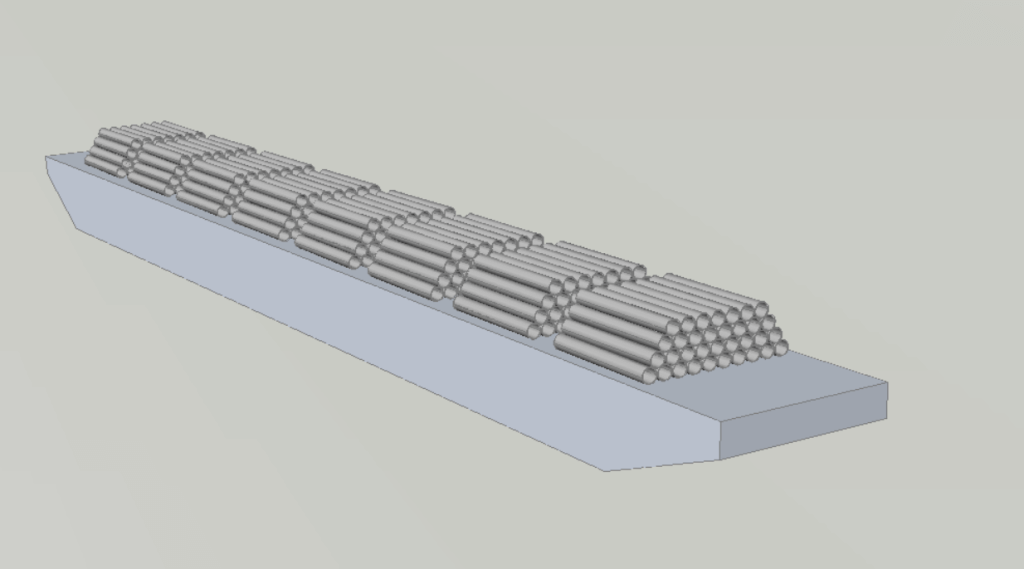

Introduction to Pipe Transportation – Part 2 (Planning & Scheduling)

In Part 1, we looked at the properties of pipes. In this section, we will be looking at the Planning & Scheduling of a pipe transportation operation (see below, Phase 1 & 2) SECTION 2: PLANNING, SCHEDULING, AND ENGINEERING FOR A PIPE TRANSPORT PROJECT Source:...

Pipe Transportation – An Introduction (Part 1)

(To read Part 2, click here) This is the first part in the 3-part series on Pipe Transportation. In this part we will discuss about pipes and their properties. In this article, we will talk about the transportation of pipes on ships. Pipes are needed for various...

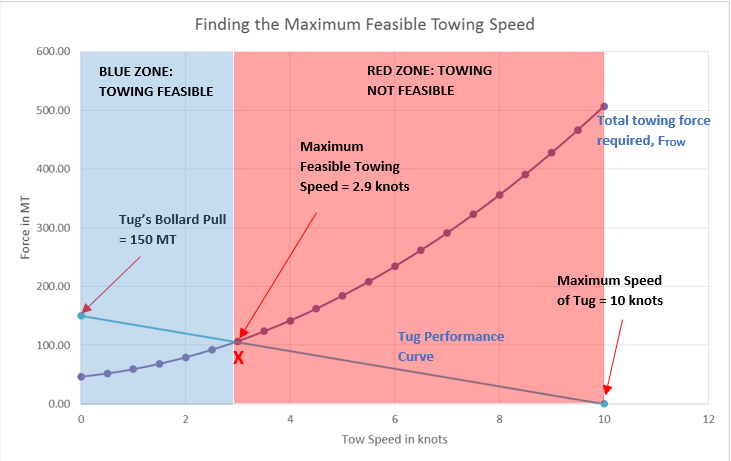

Bollard Pull Calculations – an Introduction (Part II)

Bollard Pull Calculations for Towing Operations Part II - Finding out the maximum feasible tow speed (To read Part I, please click here) Introduction This is Part - II of the two part article on Bollard Pull calculations. In the Part I we saw how to calculate the...

Bollard Pull Calculations – an Introduction (Part I)

Bollard Pull calculation is one of the most frequent calculations performed in marine towing operations. Towing operations involve the pulling of a vessel (it can be a barge, ship or an offshore structure) using another vessel (usually a tug).

Incredible read Dr Chary

Remarkable article I think.