Introduction

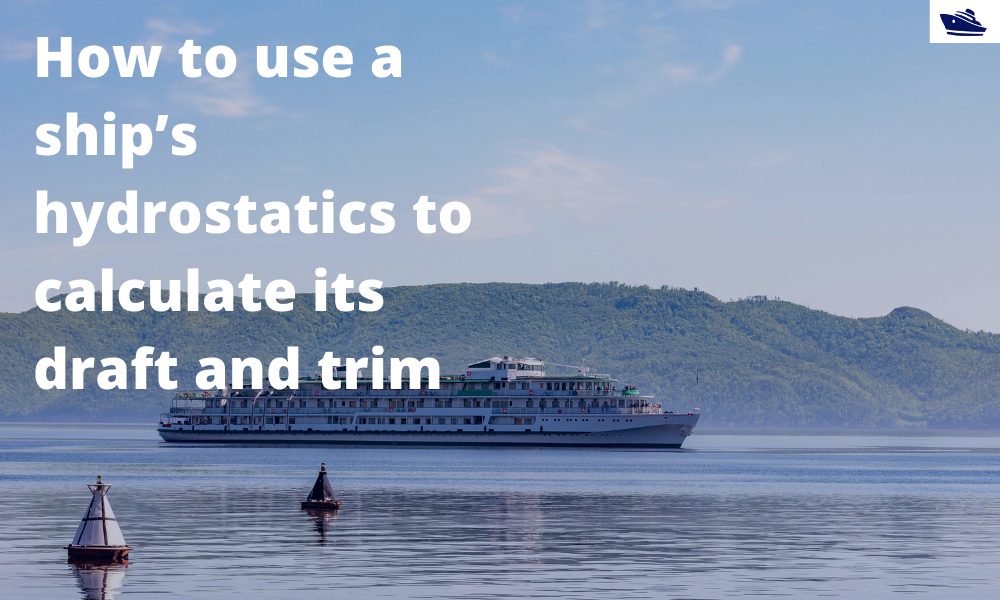

A ship’s hydrostatics, or hydrostats, is an oft used term in maritime parlance, and it refers to the characteristics when it is floating. What characteristics are these? How are these determined, and how can we read and understand them? Understanding hydrostatics helps in many ways, viz

- We can find out the floating draft and trim and many other hydrostatic parameters of a ship by knowing hydrostatics, without having to physically measure them

- A preliminary evaluation of the stability of the ship can be made by looking at the hydrostatics

As a vessel is loaded, the draft and trim of the vessel keep changing with the weight and location of the loads. Loads can be cargo, passengers, fuel, ballast, etc. and these keep varying during the voyage of the vessel.

If I were to fill the tanks with a certain %age filling, add cargo to holds, and ballast the vessel to a given arrangement, how do I know what draft and trim the vessel stands at? Of course, measuring the drafts physically every time is not practicable. The simple way is to use the table of hydrostatics. In this article, we’ll discuss what hydrostatics are and how to use them to calculate the draft and trim of the vessel.

Hydrostatic Properties – Draft

What are some of the key hydrostatic properties that one may be interested in?

The water level at which the ship is floating is called the ‘draft’ of the vessel. Also, if we load the vessel so that the weight of the forward part of the vessel is higher than that of the aft part (e.g., loading the forward holds more), then the forward part of the vessel will sink more compared to the aft, leading to the water level (draft) in the forward to be more than that in the aft. This tilt is called ‘trim’ of the vessel, and it is measured by the difference in drafts in the forward and aft ends of the vessel.

Let’s start with a simple exercise of finding out the draft and trim.

- Step 1 – Finding out the Weight and Center of Gravity (CoG) – We begin with the weights on the ship, and the center of gravity of the weights. Following are the weights we need to account for:

- Self-weight of the ship excluding all fillings in tanks – this is called the lightweight of the ship. This is obtained from the inclining experiment of the ship which is a one-time exercise to yield the weight and center of gravity of the self-weight of the ship

- Weights in tanks – fuel, cargo, bilge, ballast, crew and provisions etc. These are together termed as ‘deadweight’

- Once we know the lightweight of the ship (from inclining experiment) together with the deadweight items, we can tabulate all the weight items and their individual CoG’s and then calculate the total weight and CoG of the entire vessel in the above ‘loading condition’

- Step 2 – Once we have the weight and CoG of the vessel in the given loading condition, the next step is to open the table of hydrostatics of the vessel and read the draft from there.

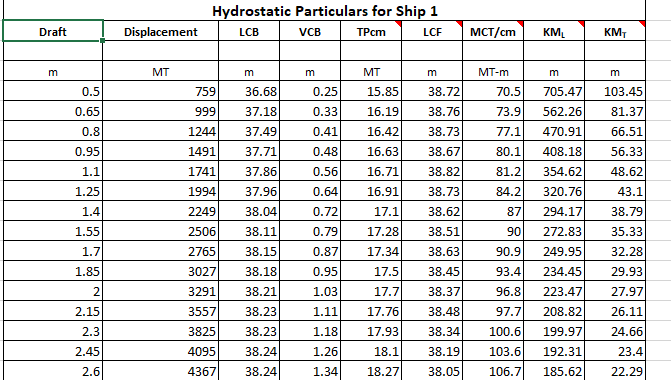

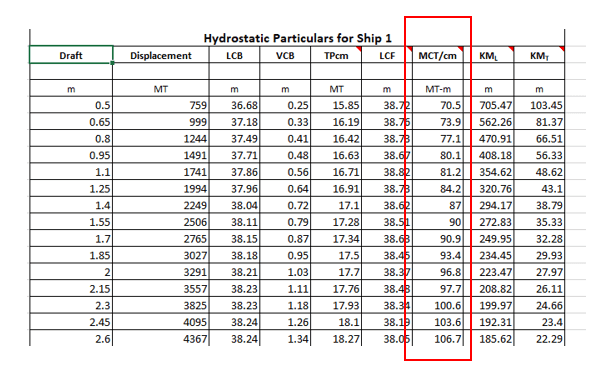

A table of hydrostatics will look like the below:

We can see that the first column is the draft spaced at equal intervals (in this case the interval is 0.15 m).

The second column is displacement. Once we have calculated the weight of the vessel in Step 1, that weight becomes the displacement. Thus,

* The hydrostatics table is for a given trim. Generally, the hydrostatics available are for the zero-trim condition, and the same are used to demonstrate the calculation in this article.

*Displacement = weight of the vessel in the floating condition (including deadweight)

Now, to read the draft, we need to look up the corresponding draft for the displacement value calculated in Step 1.

For example, if the displacement calculated was 1994 MT, then the draft is 1.25 m, and if the displacement was 2249 MT, then the draft will be 1.4 m.

However, what if the displacement calculated falls in-between two values listed in the hydrostatic table, say, 2220 MT?

In that case, we can find the draft by linear interpolation. For the above case, the displacement of 2220 MT falls between the displacement values 1994 MT and 2249 MT in the table. These displacements and their corresponding drafts are specified below:

| Displacement | Draft |

| D1 = 1994 | T1 = 1.25 |

| D2 = 2249 | T2 = 1.4 |

| D = 2240 | T = ? |

The interpolation formula is

T = T1 + (D – D1)/(D2 – D1) * (T2 – T1)

Which gives

T, draft at 2240 MT displacement = 1.25 + (2240 – 1994)/(2249 – 1994) x (1.4 – 1.25)

- T = 1.394 m

So, we have computed the draft from the hydrostatics table. However, this draft is measured at the LCF (Longitudinal Center of Floatation) of the vessel which is close to the midship and is also called the mean draft. The drafts at the two ends of the vessel may vary depending on whether the vessel experiences a trim too. To get accurate drafts at the ends of the vessel, we need to find out the trim of the vessel too. Let’s see how to get it from the hydrostats.

Hydrostatic Properties – Trim

The Trim of a vessel is the angle by which the ship tilts in a loading condition relative to its baseline. If the waterline is not parallel to the baseline of the vessel, then the vessel trims. The value of trim depends on how the vessel is loaded. If the aft of the vessel is heavier, then the draft at aft will be higher, and the vessel is said to ‘trim by aft’. Similarly, if the weight of the forward is higher, it ‘trims by forward’.

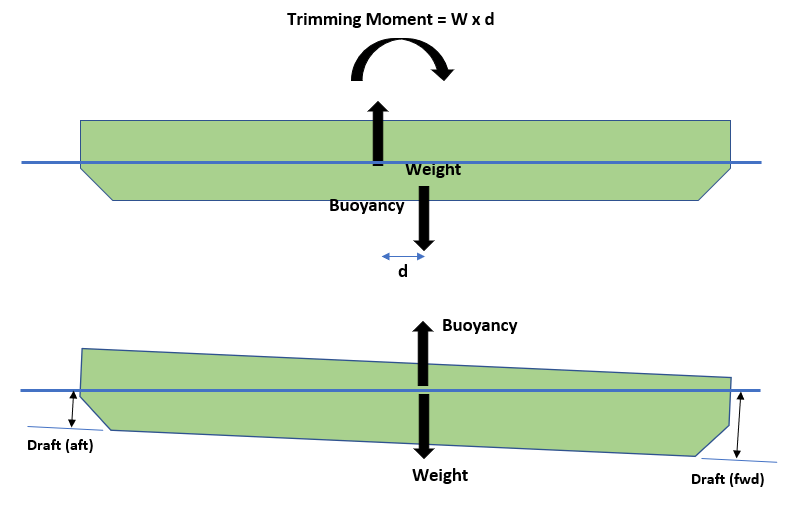

What causes the trim? If we look at the picture below, it shows the two fundamental forces acting on the ship: 1) The ship’s own weight acting downwards 2) The buoyancy of the submerged part of the ship. The vessel will not experience any trim if the two forces are acting along the same vertical at the same location along the vessel’s length. What happens if they are not acting at the same location but separated apart?

Looking at the figure below, the upward buoyancy force and the downwards weight force will lead to a turning moment on the ship. This ‘trimming’ moment will tend to tilt the ship till the weight and buoyancy forces align.

We can see that in the final condition the draft at fwd is more than the draft at the aft.

The trim is given by the difference in the drafts fwd and aft. In the above case, it will be ‘trim by fwd’.

In degrees, the trim is given by

Trim (degrees) = tan-1[(draft fwd – draft aft)/Length of ship]

Calculating Trim

We can see that we need the forward and aft drafts to calculate the trim. However, the draft available for us from the hydrostatic table is the draft at LCF (around midship). How do we calculate the trim then?

Any trim is caused by a trimming moment. As highlighted earlier, this trimming moment equals the Displacement of the vessel multiplied by the longitudinal distance between the Center of Gravity and Center of Buoyancy.

Trimming moment = Displacement x (LCG – LCB)

When the LCG is forward of the LCB, then the vessel trims by fwd, and when the LCG is aft of the LCB, then the vessel trims by aft.

Once we have the trimming moment, the next step is to look at the hydrostatic parameter called Moment to Change Trim by 1 cm (MCTcm).

If we look at hydrostats again, we can see that there is a parameter called the Moment to Change Trim by 1 cm, called MCTcm. It is measured in the units of MT-m. Basically, to trim the vessel by 1 cm (where 1 cm is the difference in the drafts aft and fwd) we need to apply an overturning moment on the vessel. This moment depends on the waterplane of the draft at which the vessel is floating (the detailed calculation of MCTcm is out of the purview of this article).

The trim can be calculated by dividing the trimming moment by the MCTcm. This will give the total trim in cm.

Let’s look at an example. If the vessel is floating at, say, 1.1 m draft, then the following are the hydrostats:

- Displacement = 1741 MT

- LCB – the longitudinal center of buoyancy = 37.86 m. In this table, LCB is measured from the aft of the vessel, positive forward. The LCB measurement can be from other locations like midship or fwd end too.

- MCTcm = 81.2 MT-m

Now, we take two scenarios, depending on the location of the LCG:

- Case 1 – when LCG is fwd of LCB, say at 40 m from the aft of the vessel. In this case, the trimming moment is

Trimming moment = 1741 x (40 -37.86) = 3725.74 MT-m by FWD

Thus, the trim is

Trim = 3725.74/MCTcm = 3725.4/81.2 cm = 45.88 cm by FWD

Thus, the vessel is trimming by forward by 45.88 cm. This means that the difference between the drafts fwd and aft is 45.88 cm.

- Case 2 – when LCG is aft of LCB, say at 35 m from the aft of the vessel. In this case, the trimming moment is

Trimming moment = 1741 (Displacement) x (37.86 – 35) = 4979.26 MT-m by AFT

Thus, the trim is

Trim = 4979.26/MCTcm = 3725.4/81.2 cm = 61.32 cm by AFT

Thus, the vessel is trimming by aft by 61.32 cm. This means that the difference between the drafts aft and fwd is 61.32 cm.

Calculating the drafts aft and fwd from trim

Now we have the total trim, i.e., the difference between the drafts at aft and fwd. We also have the mean draft of the vessel which we obtained from the hydrostatics table. How do we get the drafts at the aft and fwd of the vessel?

As specified earlier, the draft measured is at the location of the LCF of the vessel. The following picture depicts the mean draft and the total trim of the vessel. We can see that the total trim is t = tf – ta which is measured over the length between perpendiculars (LBP) of the vessel.

Calculating backward, we can get the following relations:

ta = tm – LCF/LBP x t

tf = tm + (LBP – LCF)/LBP x t

That was about calculating the draft and trim of a vessel from its hydrostats. This can be helpful for quick evaluations of the floating position of the vessel when it is loaded.

Disclaimer: This post is not meant to be authoritative writing on the topic presented. thenavalarch bears no responsibility for the accuracy of this article, or for any incidents/losses arising due to the use of the information in this article in any operation. It is recommended to seek professional advice before executing any activity which draws on information mentioned in this post. All the figures, drawings, and pictures are property of thenavalarch except where indicated, and may not be copied or distributed without permission.

Using MS Excel to evaluate the Stability of existing Barges

Barges are the simplest, and yet most widely used of marine vehicles. They are used for a variety of purposes ranging from carrying cargo in bulk or liquid, to even carrying passengers for short inland cruises. Barges are mostly towed by another barge called a tug,...

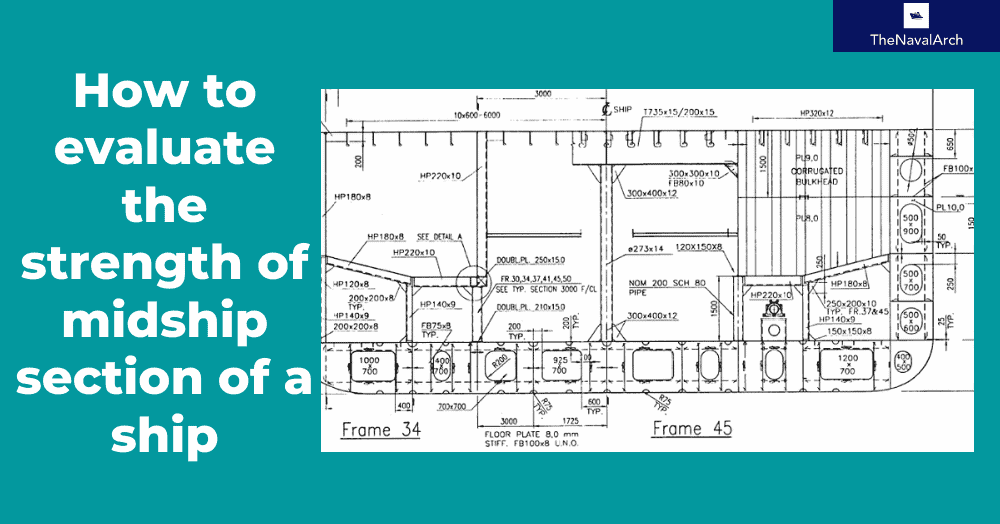

How to calculate the strength of Midship Section of a Ship

The mid-ship section of a ship is a defining structural drawing of the vessel. It represents the most critical structural parameter of the vessel – its global strength. To assess how much of the bending moment (hog and sag) the vessel can tolerate, it is important to...

How to use empirical formulas to estimate the resistance of a Ship

How to use empirical formulas to estimate the resistance of a Ship Resistance estimation holds immense importance in the design stage of a vessel. Based on the results of the resistance estimation of a vessel, the selection of the right propulsion system is done....

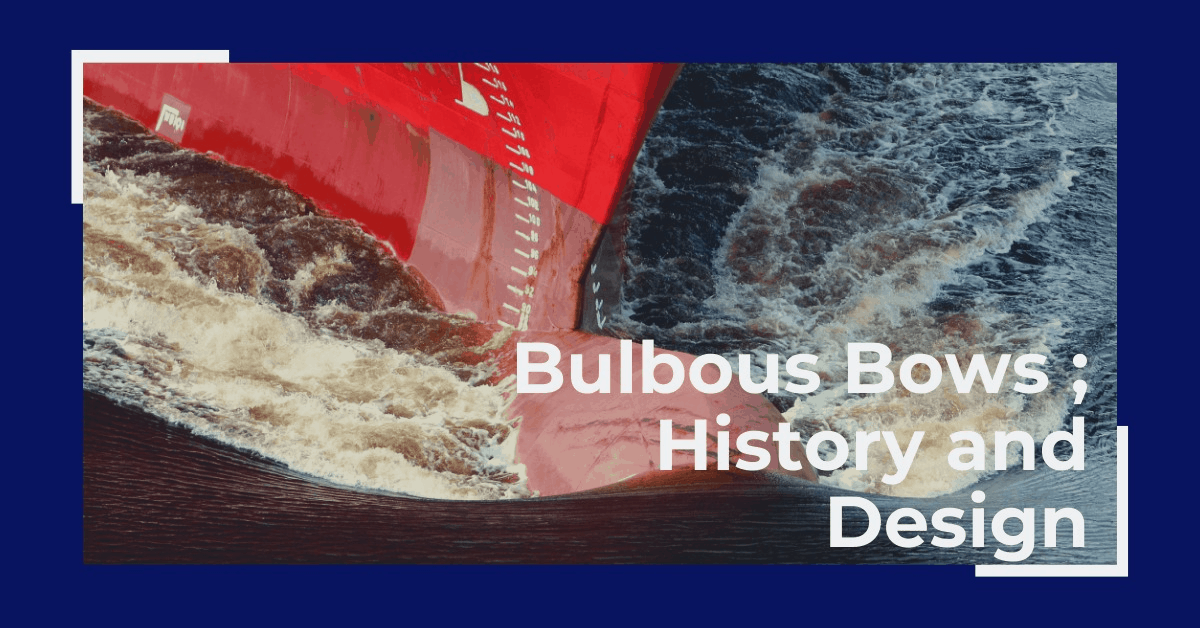

Bulbous Bows – History and Design

by Bijit Sarkar, Naval Architect Introduction The eternal search of a naval architect – a perfect bow. Sadly, it never exists. Different bow forms are good for different types, sizes of vessels and seaways. What does a naval architect want out of the bow he designs?...

Designing a pad-eye: little items with big intricacies

Pad-eyes are one of the smallest and most universally used structural items in the maritime and Oil & Gas industry. They are used for a variety of purposes too: from a simple seafastening of a cargo to deck of a vessel, to complicated lifting operations involving...

Cathodic Protection – Ships, Offshore Platforms, FPSO’s and Pipelines: a comparison

Cathodic protection of a structure is an exercise which requires close study of the structure on which it is going to be implemented. The type and quantity of cathodic protection by anodes will depend upon multiple factors: the Geometry of the Structure, the...

Role of a naval architect – a walkthrough (Part – 1)

This is the first in a series of articles on 'Role of a Naval Architect' by Mr Bijit Sarkar, a Naval Architect with 35+ years of experience in ship design and shipbuilding. I would define a naval architect as one who has the ability to greet the client as he/she walks...

The bulbous bow – why some ships have it and others don’t

By Tamal Mukherjee, This is the Part 1 of a two part article on the Bulbous Bow. Part 2 can be accessed here *This article originally appeared in May 2019 edition of Marine Engineers Review (India), the Journal of Institute of Marine Engineers India. It is being...

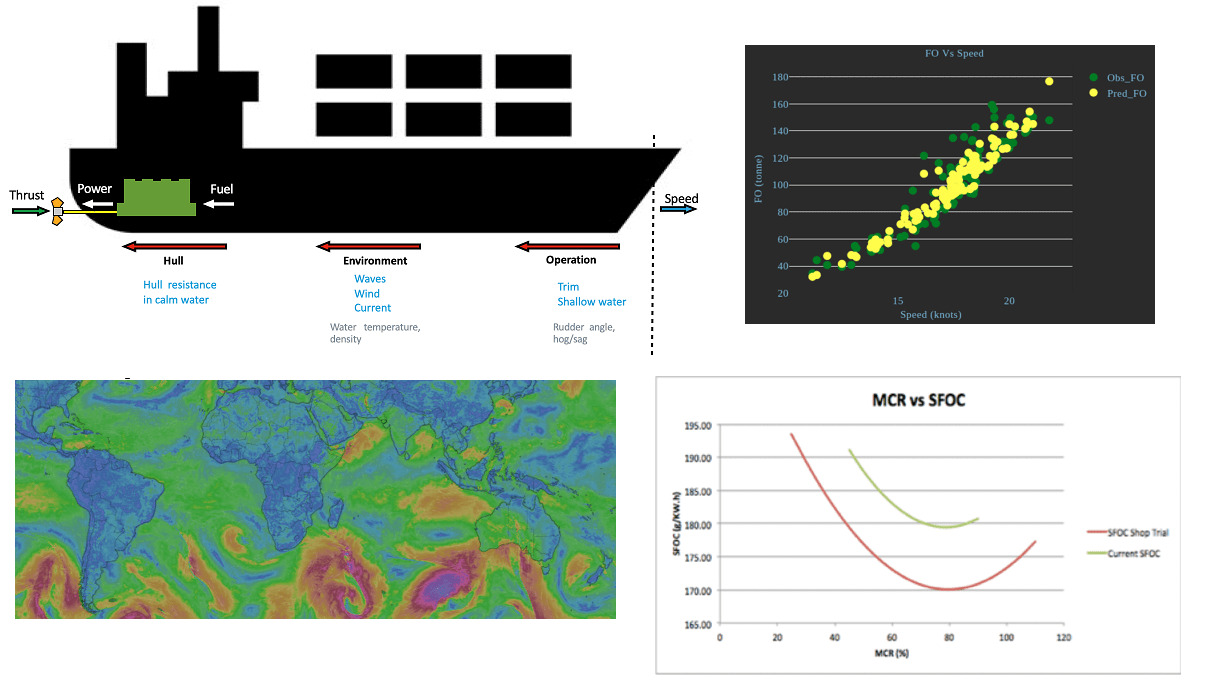

Removing Human Error in Ship Performance Analysis

Introduction Shipping is the most dominant means of transport that facilitate global trade. Over 90% of world trade is done by ships[1]. Fuel onboard ships, commonly referred to as "bunkers", has become the largest cost item of a ship's Operational Expenses (OPEX),...

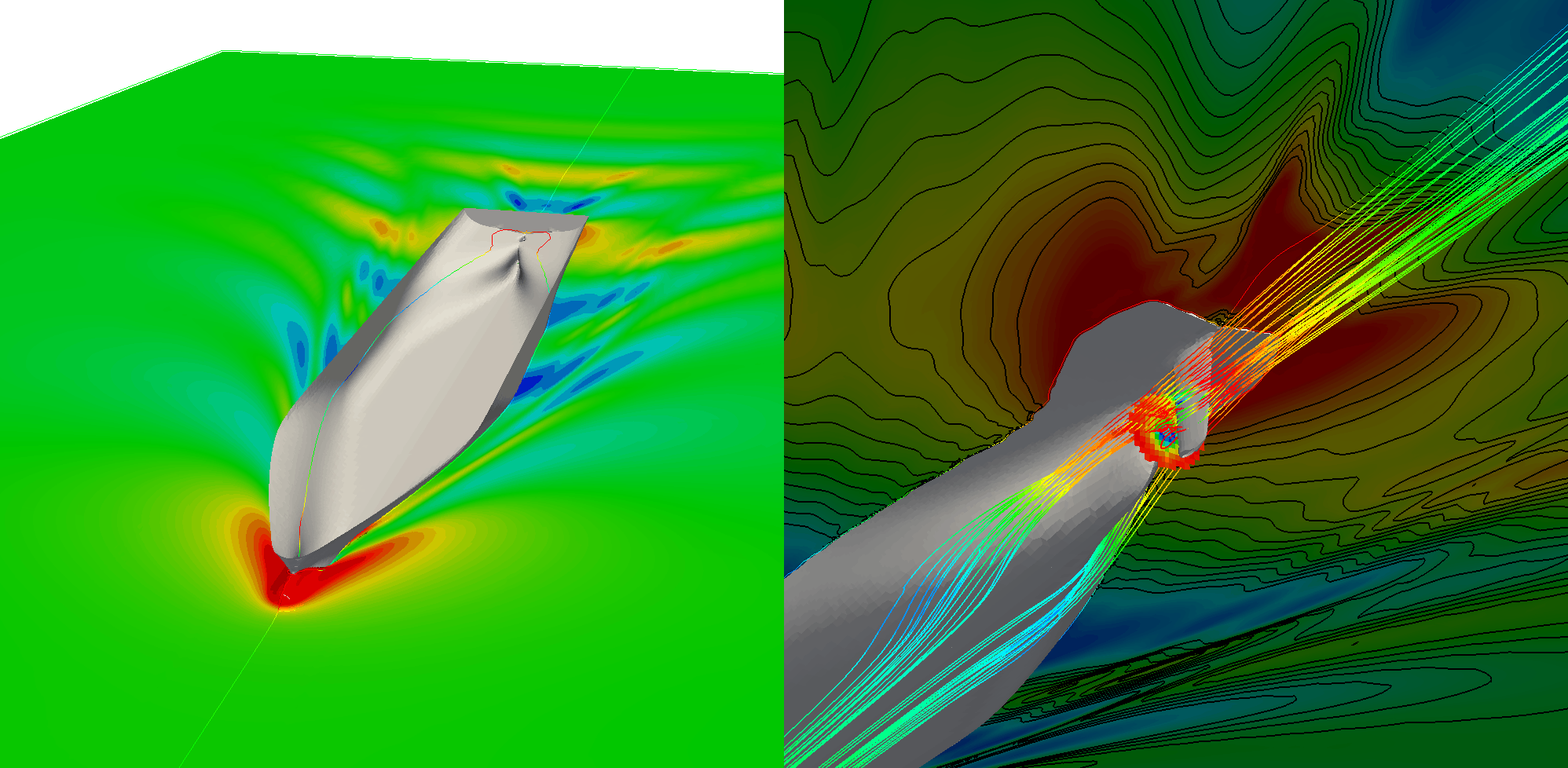

CFD in the marine industry: today and tomorrow

In the world of advancing digital technology, it important to identify all the best ways to apply it to the extremely complex task of designing a ship. Riding the wave of the rapid progress of High Performance Computing, Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD)...

Thank you very much

for calculation

Thank you

I want to learn how to calculate the trim

Hi Jemil

Please go through any basic naval architecture book and you’ll learn. All the best!

Do you have a simple way I can calculate my trim and draft for my vessel

wrong interpolation formula, it should be:

T = T1 + (D – D1)*[(T2 – T1)/(D2 – D1)]